Last week I took a look at the kind of advertising you might have found if browsing through an issue of Betty’s Paper, a popular magazine from the 1920s through to (I think) about the 1940s. It’s hard to find out much about the mag without doing some hardcore research (it might come to that), but I know it was at its peak in the 30s, and there are still quite a few issues left to be snapped up if you’re of a mind to buy this kind of memorabilia.

Last week I took a look at the kind of advertising you might have found if browsing through an issue of Betty’s Paper, a popular magazine from the 1920s through to (I think) about the 1940s. It’s hard to find out much about the mag without doing some hardcore research (it might come to that), but I know it was at its peak in the 30s, and there are still quite a few issues left to be snapped up if you’re of a mind to buy this kind of memorabilia.

Betty’s Paper wasn’t the only one around. There was also Peg’s Paper (1919 to 40) English Woman’s Journal (1850s to 1910), The Gentlewoman (1890 to 1926), The Freewoman (1911 to 1912), The Lady’s Realm (1890s to 1914), Time and Tide (1920s to 1970s), Woman’s Journal (1920 to 2001) to name the most well known. There were others, often with a more targeted purpose, for example, campaigning women’s suffrage and letting women know what was happening in various groups. Mostly magazines were aimed at middle and upper class women, but Peg’s Paper, and Betty’s Paper were aimed at working class women, and had less educational and more purely entertaining content than other magazines.

Betty’s – and Peg’s – contained short fiction, sometimes as serials, that thrilled the imagination, and owed a great deal to the cinema. There were fashion and style tips, using actresses of the era as role models, and holding them up as examples of the right look to emulate, very much as all the media do today. We looked at the ads last week, and I concluded that, again just as now, many were fixated upon appearance: looking slim, budget fashion that stood up to scrutiny, easy health fixes for people who lived busy lives, working hard and with little time or money to spend on themselves. Perfect for the factory and domestic girls of the 1920s and 1930s.

But what were the stories like that were every week there to tantalise our girls as they took a quick tea break or read for ten minutes before going to sleep?

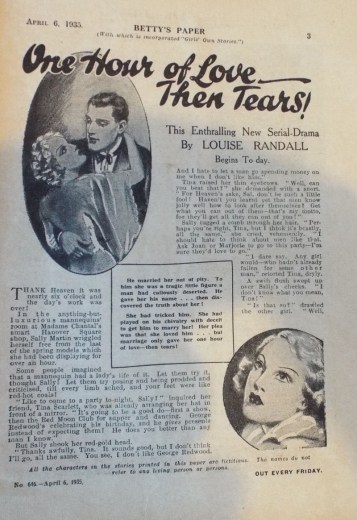

Firstly, I noticed that the stories were illustrated, a bit like a children’s comic. I know that still happens today, but these struck me as being more dramatic. The men often seem to loom over the women in a authoritative almost aggressive manner. The men also look very old compared to the younger-looking women. Pretty sure all these heroines are about 20 and all the heroes are about 48.

The headlines and taglines too were melodramatic and leaning towards the scandalous. I presume this was a good way to draw in readers and get them to spend their cash – Betty’s Paper was tuppence ‘Every Friday’. When wages were paid weekly in cash, I imagine this was one of the first ‘treats’ a girl would get herself before going home and giving most of her money to her parents.

Anyway – on to the stories. I’ve only got two issues (at the moment hahaha) but between these two issues of 36 pages each, there are eight stories, and seem to be serialised in two or three parts. Some of them masquerade as ‘real life stories’ (see me next week for more…) but the rest are presented as written by ‘well-known’ lady authors. The sensational headings are guaranteed to pique the interest of any normal woman: ‘One Hour of Love Then Tears’, ‘The Sin That Came Between Them’, ‘When Men Are Dangerous’, ‘But She Was Blamed’, and my particular favourite, ‘Back Street Blonde’, tagline ‘she was born to be a man’s girl’.

They read a bit like cautionary tales – be careful, be cautious, be modest, they seem to say. Keep away from MEN. And like Mary Bennett in Pride and Prejudice, they seem to hint vaguely at the dreadful fate that awaits a woman without virtue. This was probably useful information for a young woman with a little bit of her own money able to go out with her friends in the evening in the wicked city and not come home until – ooh – ten? eleven o’clock? The stories are about trying very hard to make a marriage work, about being honest, and morally upright, about protecting your home and family. So they are aspirational, inspirational and improving. But they can be a bit juicy, as this picture seems to show: ‘Guy held her close in his arms. ”I don’t care about anything else–I want you, Dawn,’ he whispered.” Oh Dawn, get out girl, while you can!

Mostly I’m in awe of the writers. Week after week they turned out 5000 words or maybe more, and (I assume) got paid for it. I’ve tried Googling some of the authors whose work features in these magazines: Denise Egerton (Secret Bride), Louise Randall (One Hour of Love – Then Tears), Stella Deans (The Sin That Came Between Them), Cynthia Loring (But She Was Blamed), Jasmine Day (Back Street Blonde). Of these, I’ve found a number of books from the 50s and 60s by a Denise Egerton, and they appear to be romance genre, so maybe it’s the same woman? I haven’t been able to find out anything about the others–who knows–maybe they were all Denise? Or possibly all these ‘lady writers’ were simply the pen names of a grizzled editor with pages to fill and a talent for writing totes emosh romance? I can picture him, tapping away at his typewriter until all hours, cigar ash spilling all down his shirt. I bet his real name was something like Isaac Peabody.

I think these stories offer an intriguing insight into the values and aspirations of working women in the 1920s and 1930s. They’ve actually been the subject of study in a number of British and American dissertations and publications, for example, Peg’s Paper was looked at in Class and Gender: The ‘Girls’weeklies’ by Billie Melman, a section in ‘Women and The Popular Imagination in the Twenties.’ And in this article in The Guardian by Kathryn Hughes.

But lest we forget, what they really were was an escape from the drudgery of everyday life for women with little opportunity to do anything other than dream.

***

Thanks again for your ’20’s and ’30’s stories. reminds me of my Mum . I have a picture of her with friends having a happy time about then.

Aww – old photos are wonderful!

Loved the article on the 1930’s magazine stories, very interesting. Thank you.

Thank you Pam, I’m so glad you enjoyed it. I’m not always sure how much other people will enjoy the things I like!

Such an interesting article.

Oh thank you Myra! I’ve fixed the typos that I forgot to check for yesterday!